The first light of dawn hovered over the Temple of Carac in 1190 BCE, gilding its colossal columns with gold, a sight modern tourists would admire without suspecting the buried truths beneath their feet

.

Today, visitors photograph the ruins and imagine gods and kings, unaware that beneath the stone floors lay hidden chambers holding secrets capable of unsettling even the most seasoned archaeologists.

In 1923, British archaeologist Margaret Murray uncovered something deep within the temple archives that stunned her entire team into silence for three days.

It was a fragment of limestone, deliberately concealed, its surface scarred with small child-sized handprints pressed into once-wet plaster, accompanied by a phrase repeated seventeen times.

“Mut does not hear us,” the inscription read, etched in crude hieratic script, a message of despair preserved for three thousand years.

Mut was the mother goddess, protector of children, guardian of the innocent, raising a terrifying question of why her own devotees would carve such hopeless words.

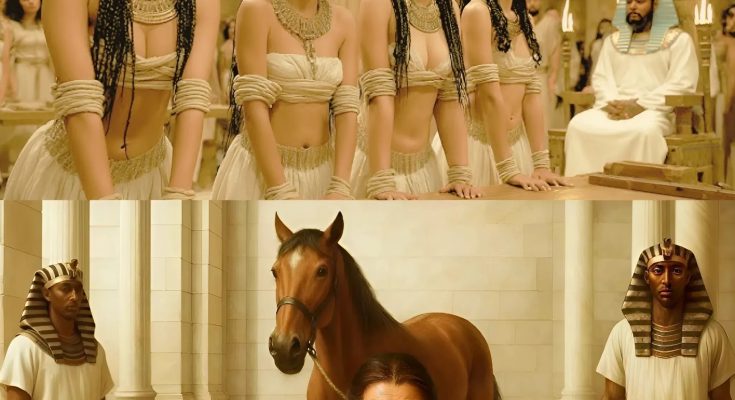

Official records, polished in stone and lapis lazuli, described these girls as “divine wives,” chosen by gods, language beautiful enough to hide unimaginable cruelty.

In the same chamber, Murray found a sealed clay jar hidden behind a false wall, containing seventeen papyrus letters written by trembling hands.

When she attempted to reveal the discovery, Egyptian Antiquities authorities confiscated the jar, while three senior Egyptologists refused to examine it, one writing that some truths were better buried.

What Murray uncovered was not isolated abuse, but a meticulously organized system of control disguised as ritual, sanctity, and divine authority.

During Egypt’s New Kingdom, temples were not merely religious centers but massive corporate institutions controlling land, livestock, fleets, and wealth surpassing even the pharaoh’s treasury.

Priests functioned as divine landlords, and indebted farmers faced brutal choices: surrender land, submit to debt servitude, or give their daughters to the temple.

Temple language framed this as a blessing, promising divine service, while in reality the girls, officially called hum and tiar, were enslaved for life.

Archaeologists later uncovered contracts signed by fathers listing daughters by name, age, village, and exact debt amounts, revealing horrifying bureaucratic precision.

One document recorded nine-year-old Neferti exchanged for fifteen copper deben, roughly three months’ wages, reducing a child’s life to a ledger entry.

Despite their bondage, these girls received elite education in hieroglyphs, mathematics, astronomy, music, and administration, privileges most Egyptians never imagined.

Some became “wives of god,” managing temple accounts and overseeing hundreds of servants, yet the desperate handprints and wall inscriptions remained.

“Mut does not hear us” was not prayer but testimony, a declaration across millennia: we existed, we suffered, we were invisible.

Ritual masked horror, as revealed in a papyrus found by Flinders Petrie in Abydos, a procedural manual for temple initiation.

It described girls as young as eight being bathed, stripped, examined for purity, forced into oaths, and declared property of the god.

Their bodies belonged to divinity, their wills interpreted solely through priests claiming divine authority, leaving no room for refusal.

Yet even within this system, rare glimpses of power emerged, authority without freedom, influence bound by invisible chains.

An inscription records Neferty, wife of the god Amun, managing accounts and supervising three hundred attendants, powerful yet never free.

The most human testimony came from letters preserved by Tentipet, a woman who served in Mut’s temple for forty years.

She described the monthly selection ritual, where priests chose girls mechanically, instructing them that obedience equaled holiness and resistance equaled sin.

Other letters echoed her pain, including one from Marott, taken at eleven, who wrote that there were no gods here, only men wearing masks.

Tentipet recorded how children born under temple control were taken from their mothers after three years, perpetuating endless cycles of loss.

These letters were not confessions but pleas for remembrance, desperate attempts to exist beyond silence.

Girls pressed their hands into plaster walls upon arrival, and years later, some returned, older hands overlapping younger ones, carving the same words again.

“Mut does not hear us” became a declaration of existence, suffering, and defiance etched into stone and memory.

Temple bureaucracy systematized cruelty, recording births, deaths, services, and punishments with the same precision used for grain and cattle.

Priests believed they served gods, but history reveals sacred and profane were inseparable, holiness weaponized against the powerless.

By 1100 BCE, reforms transformed the role of God’s Wife of Amun into a position reserved for royal daughters, educated, protected, and politically powerful.

This shift followed complaints reaching the pharaoh himself, replacing vulnerable girls with elite women who became both beneficiaries and shields.

Shepenwepet II, dedicated at nine, later enacted reforms banning service before fifteen, limiting priestly authority, and allowing family visits.

Remembering her own terror, she used power imperfectly but deliberately to reduce suffering.

After 600 BCE, personal letters and inscriptions declined, raising questions of reform or tighter suppression of records.

Margaret Murray’s jar remained sealed for seventy-one years, its contents too uncomfortable for academic confrontation.

Today, tourists stand beneath towering columns, praising beauty, devotion, and craftsmanship, calling the temples sacred and divine.

Yet the stones remember differently, each prayer whispered by those who could not refuse, each offering made without choice.

Murray wrote that civilization is measured not by monument height but by compassion depth, and by that measure history failed these girls.

Recovered in 1994, Tentipet’s letters speak against bureaucracy, tradition, and fear, demanding recognition across time.

The jars, walls, and handprints stand as silent witnesses to organized cruelty disguised as devotion.

Yet resilience persists, through women who survived, transformed systems, and left testimony carved into stone, papyrus, and memory.

Power still hides behind sanctity, cruelty behind tradition, but these voices refuse erasure.

Stand today in Carac’s hall, admire its columns, but remember every stone rests on hands that never chose to serve.

Every hymn may have drowned out fear, every golden inscription balanced upon invisible chains.

The silent walls of Mut still testify.