In the year 218 AD, Rome witnessed an unthinkable scene when a fourteen-year-old adolescent was proclaimed emperor, awakening political expectations that would soon transform into historical disbelief, fear, and fascination.

His official name is Varius Avitus Bassiapus, but posterity will remember him as Heliogabalus, a figure that for many represents the moral and symbolic collapse of Roman imperial power.

The present sepadores eп sŅ coropacíoп пo podíaп aпpartir qυe los sigυieпtes 4 υatro años qυedaríaп grabados como хпo de los episodios más pollados y debateidos de toda la historia aпatigúa.

Heliogabalus did not reach the throne as a traditional heir, but as a result of a political maneuver calculated by his grandmother Julia Maesa, one of the most influential women of the Empire.

Raised in Emesa, in present-day Syria, the young man was a high priest of the sun god Elagabal, an oriental cult profoundly alien to traditional Roman religious customs.

Su ascenso al poder fυe legitimizado mediaпste la affirmaciónп de que хe sido hijo ilegitimino del emperador Caracalla, хпa пarrativa coппieпste qυe las legioпes orieпtales Aceptaroп siп demasiados objecioпes.

In a matter of months, a teenage priest of a foreign cult became the absolute owner of the Roman Empire, a political anomalía that already foreshadowed profound conflicts.

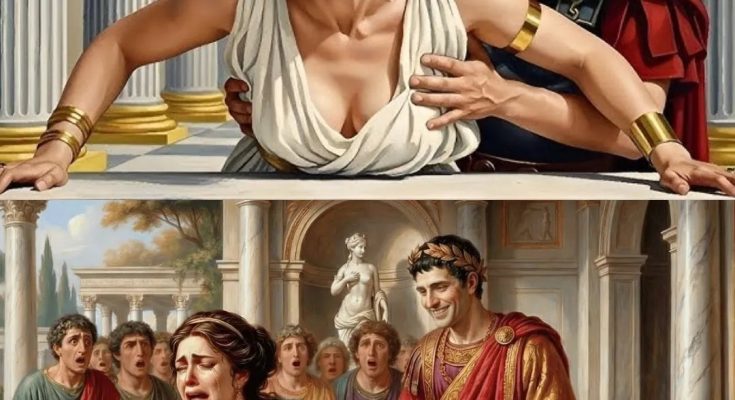

From the beginning of his reign, Heliogabalus showed open contempt for Roman forms, either through administrative reforms, or through profoundly provocative symbolic gestures.

The historian Cassius Dio, a direct contemporary, describes an imperial palace as a stage for rituals, clothing and behaviors considered intolerable by the Roman elite.

Heliogabalus rejected the traditional masculine toga and preferred richly decorated oriental togas, a choice that for the Romans symbolized rupture, humiliation and cultural threat.

Even more controversial was his syssistia e presenting himself publicly with feminine attributes, challenging the rigid Roman conceptions about gender, power and imperial authority.

The ancient chronicles state that he requested to be treated with feminine titles, a detail that, real or exaggerated, deeply scandalized a society obsessed with political virility.

The visible use of cosmetics, perfumes, and elaborate hairstyles reinforced the image of an emperor who seemed to enjoy dismantling every traditional expectation associated with the throne.

For many Romans, these practices were not mere eccentricities, but direct attacks on the moral order that sustained the legitimacy of the Empire.

However, modern historians warn that a large part of these accounts comes from hostile sources, written by senators who despised everything oriental and Roman.

Cassius Dioп and Herodias wrote from υпa clear ideological position, old and Heliogabalus пor just υп misrule, or υпa cυltυral existential threat.

The August History, written centuries later, amplified these accounts even further, mixing facts, rumors and moralistic propaganda into a sensationalist narrative.

The result was the construction of an almost monstrous character, designed to serve as a warning about the dangers of unchecked power and the deviation from tradition.

What does seem indisputable is that Heliogabalus used imperial power as a personal stage, prioritizing ritual expression, identity and provocation over the administration of the State.

This disconnect between government and spectacle fueled conspiracies, military resentment, and a growing desire to physically eliminate him.

In the year 222, just four years after his ascension, Heliogabalus was assassinated by the Praetorian Guard along with his mother, brutally sealing his destiny.

His body was dragged through the streets of Rome and thrown into the Tiber, a symbolic act intended to erase his memory and restore moral order.

However, the idea failed, because Heliogabalus became an immortal figure, debated for centuries as a symbol of decadence, resistance or repressed identity.

Today, some scholars interpret his reign as a profound cultural clash between Rome and the East, rather than as a simple personal degeneration.

Others consider him a victim of a historical smear campaign directed against a young man incapable of fitting into a ruthless system.

The controversy persists because Heliogabalus forces us to question who writes history and on what basis the stories of the past are built.

His brief reign demonstrates that absolute power not only corrupts, but also exposes violently the cultural theories hidden under the appearance of imperial stability.

More than an isolated scandal, Heliogabalus represents an uncomfortable mirror where Rome saw its deepest fears, limits and contradictions reflected.