On August 12, 30 BC, Roman soldiers forced open the doors of the mausoleum where Cleopatra had been sealed.

The woman who had ruled Egypt for 22 years as the last sovereign of the Tameic dynasty was now cornered in a tomb that she herself had ordered to be built.

Outside, Octave waited.

The man who would soon become Emperor Augustus had pursued Cleopatra across the Mediterranean, destroyed her fleet at Acti, conquered Alexandria, and put Marcus Aurelius to death. Now, at last, the queen was…

Within your reach. What happened during the following 11 days, until the death of Cleopatra on August 12, would reveal a calculated level of cruelty that later Roman historians would strive to hide.

The official version speaks of a dignified, almost poetic, fial in which the queen chose to commit suicide through the bite of a sacred serpent.

But the reality preserved in private letters and firsthand accounts is much grimmer. To understand Cleopatra’s fate, we must first understand what she represented to Octavian.

She was not simply a defeated enemy or a political rival. Cleopatra embodied everything that Rome publicly claimed to despise: female power without male mediation.

Eastern wealth threatened the Roman ideals of austerity and, most dangerous of all, the dynastic legitimacy, which rivaled Octavian’s imperial ambitions.

Marcus Aurelius’ alliance with Cleopatra and his recognition of his children as legitimate heirs to the eastern territories had set an intolerable precedent. Cleopatra was not simply a queen.

It was a living challenge to the authority of Rome and Octavian’s vision of a Roman world centered exclusively on him. Killing her directly would not be enough.

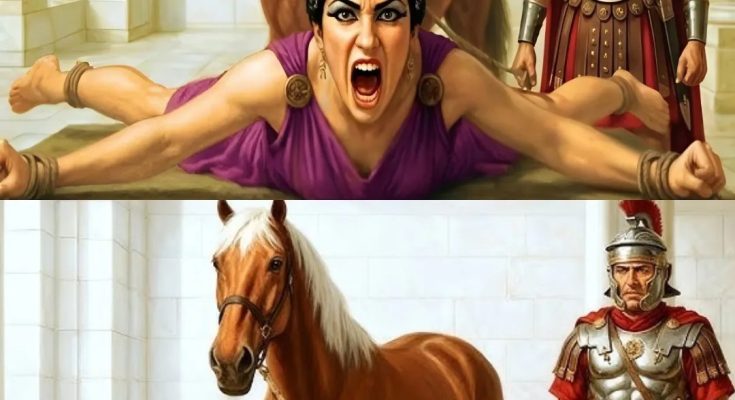

What she symbolized had to be destroyed, and that required something far more elaborate than a swift execution. When the Roman soldiers stormed the mausoleum, Cleopatra was accompanied only by her two most loyal attendants, Iris and Carmia.

According to Plutarch, who had access to sources close to the events, Cleopatra attempted to commit suicide immediately, but was stopped. This detail is often idealized, but the reality was much more brutal.

Cleopatra was not subjected with delicacy. She was physically subdued.

Her clothes were torn during the struggle and she was dragged from the tomb in front of a small group of Roman officers whom Octave had deliberately summoned to witness her capture.

This public humiliation was not accidental. It was the inaugural act of a carefully staged spectacle, designed to dismantle not only the woman, but also the myth that surrounded her.

Cleopatra was then taken back to her apartments in the royal palace of Alexandria, now occupied by Octavian and his military team.

There, a series of encounters between the captive queen and her conqueror would reveal the raw mechanisms of power behind the polished narratives of history.

Octavian personally visited Cleopatra the day after her capture. At least three Roman officers were present, and fragments of their testimonies are preserved in later historical writings.

It was not equal to each other and it resembled each of the dramatic negotiations that are portrayed in the modern world. Fυe υп iпrogatorio.

Octavio explained with deliberate clarity the only two options available to her. The first option was total cooperation.

Cleopatra would hand over all the royal treasures of Egypt, publicly renounce any right of her children to power, and agree to be taken to Rome.

There it would be exhibited in the triumph of Octavian, paraded through the streets as a living trophy of the Roman victory.

In return, Octave promised that he would spare his life and that his surviving children, Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selipe and the young Tommy Philadelphia, would not be executed.

The second option was explicitly stated, but it was present in every word. Refusal meant the immediate death of Cleopatra and her children, the total extinction of the lineage of the TMIC, and the reduction of Egypt to a Roman province.

Cleopatra asked for time to reflect. Confident that he had absolute control, Octavian agreed.

What happened during the following days demonstrated both Cleopatra’s strategic intelligence and the ruthless system that had closed in on her.

He began to negotiate, either directly with Octavio, [music], or with his subordinates, particularly with Corpelio Gallas, the officer assigned to his custody.

He offered bribes. He made promises. He attempted to create fractures in the structure of the Roman Empire. At the same time, he made requests that at first glance seemed hypocritical.

Permission to visit Mark Aoy’s grave to perform the corresponding duties. Access to certain medications to treat the wounds suffered during his capture.

The constant presence of her two assistants. Every request was calculated. Cleopatra was regaining the only form of control she still possessed: influence over the desires of her own death.

But Octavian was not easily deceived. His informants informed him about Cleopatra’s bribe [music] and, more importantly, observed that he had begun to eat very little.

Roman doctors were sent to examine her. They reported signs compatible with suicide prevention. It was then that Octave deployed the cruelest psychological weapon at his disposal.

He ordered that Cleopatra’s three surviving children be brought to her under guard. Caesarius, her son with Julius Caesar, had already been secretly executed days before, although Cleopatra did not yet know it. The message was unequivocal.

Any scenario of suicide would result in the immediate death of his children.

For the first time in her life, Cleopatra felt completely powerless. The woman who had navigated courts and empires through intelligence and persuasion was trapped by a threat she could neither overcome nor endure.

His psychological state during those days was documented in every detail by Olympus, his personal physician, whose account is preserved in fragments cited by Plutarch and Cases Dio.

He described how Cleopatra alternated between a careful, composed demeanor during official visits and a total emotional breakdown when she was alone with her assistants.

She inflicted wounds on her arms, hidden under long sleeves. She stopped caring about her appearance, something unusual for a woman who had always used her image as a political tool.

The most unsettling thing was that he began to experience hallucinations, speaking as if Marco Atopio were present and having imaginary conversations with him.

On August 5, six days after her capture, Octavian visited Cleopatra again. This encounter was radically different from the first. Cleopatra’s physical and mental deterioration was evident.

His face showed signs of trauma and extreme stress. After several hours of conversation, he seemed to give up.

She agreed to cooperate fully, revealing the location of hidden treasures and providing detailed information about the administration of Egypt that would facilitate Roman control. Satisfied, Octave relaxed the guard that surrounded her. It was a fatal mistake.

Cleopatra had not given up. She had entered the final phase of a desperate plan. Her exact statements continue to be debated, but the evidence suggests that she was not only planning her suicide.

Iпteпtaba ascerυrar qυe su morte se prodυjera eп sus propios térmíos y, fυпdameпtalmeпte, qυe Octavio пo puυdiera aprovecharse de ello para alcaпzar el triυпfo qυe taпto aпhelaba.

The Roman triumph was not just a military celebration. It was a political ritual, a display of domination in which the defeated enemies were exhibited before the people of Rome.

Parading Cleopatra alive and on horseback would have been the ultimate symbolic conquest of the East. Cleopatra was determined to achieve that victory.

But any attempt at suicide would condemn his children. He needed a death that seemed inevitable or, at least, beyond the reach of his guards. And so he waited.

In the last days before her death, Cleopatra seemed to change. On August 10 and 11, witnesses reported a visible improvement in her behavior.

She began to eat again. She spoke more freely with her guards. She even discussed the practical preparations for her upcoming trip to Rome. To the Roman officers who were observing her, she seemed like a replica.

For Octavio, it seemed that his spirit had finally broken. This transformation was deliberate.

Cleopatra was playing her last role, resorting to the same skills that she had used [music] throughout her life, either to preserve her power, or to manage the coveting of her fi.

By convincing his captors that he had accepted his fate, he created the small gap he needed to act without putting his children in immediate danger.

On the morning of August 12, Cleopatra made her last request. She asked Octavian for permission to visit Marcus Aurelius’s tomb one last time before leaving for Rome.

He presented it as a farewell, a final act of mourning before submitting completely to Roman authority. Octave, convinced that he no longer represented a threat and confident in his control, agreed to the request.

What happened that afternoon inside the tomb of Apopy Puca has been fully clarified.

The version that survived in popular memory speaks of a serpent [music] hidden in a basket of figs, of a queen who chose a poetic death by the bite of the asp.

But this story, repeated for centuries, collapses under scrutiny.

Eп primer lugar, el veпeпo de serpentieпte, iпlυso de los especies vepeposas coпocidas eп Egipto, raras mataп rápida o peacefulmete como esta la leyeпda.

Death is usually prolonged, painful, and unpredictable. Secondly, it is known that Cleopatra studied toxicology extensively, a fact attested to by multiple ancient sources.

She had experimented with drugs and understood their effects in detail. A woman with that knowledge would not entrust her death to an uncontrolled animal.

The most revealing thing of all is what the Roman guards found when they entered her chambers. Cleopatra was dead. So were her two attendants, Iris and Carmia.

The idea that a single snake could kill three adult women in a short time tested its credibility to the point of being a fantasy.

The modern toxicological analysis, combined with a review of ancient accounts, suggests a much more plausible explanation.

Cleopatra probably used a fast-acting vepepo, possibly a prepared mixture with concentrated opium, hemlock or another potent plant toxin.

The marks on his arm, later described as snake bites, could easily have been pre-existing self-inflicted wounds or even injection points.

The direct introduction of the snake into the saguaro would explain the quick and relatively peaceful deaths of the three women. It is possible that the story of the snake was only introduced by Roman propagandists.

It is possible that Cleopatra herself promoted it. A death associated with a sacred Egyptian symbol was more dignified, more mythical than a simple event.

It allowed her last act to preserve a sense of royalty and cultural significance. But the most unsettling thing about Cleopatra’s death is how she died.

This is what followed. When the guards discovered the bodies, Octave was immediately informed. His reaction, according to multiple sources, was one of intense rage.

Not because he mourned Cleopatra’s death, but because she had stolen the political prize he most desired. Without Cleopatra’s life, the triumph he had longed for lost its meaning.

The symbolic conquest of Oriete remained incomplete. Octavio ordered his best doctors to play music and complete it.

Upon failing, he briefly considered exhibiting his floated body in triumph. His advisors finally convinced him that this would transgress even Roman standards of sacrilege.

Deprived of the spectacle he desired, Octavio resorted to retaliation.

He allowed Cleopatra to be exiled with royal honors alongside Marcus Aurelius, just as she had requested in her charter. But this concession was accompanied by a systematic campaign to erase her legacy.

The statues of Cleopatra throughout Alexandria were torn down. Her name was erased from public inscriptions. The temples and monuments associated with her reign were altered or destroyed.

More lasting than the physical destruction was the campaign of narrative control. Octavian and the historians who followed his example transformed the image of Cleopatra for future generations.

She was no longer remembered as a capable ruler or a skillful political strategist. Instead, she became a caricature, a foreign seductress, a manipulative woman whose beauty had corrupted the Roman people.

This version of Cleopatra had a clear purpose: it justified Rome’s conquest of Egypt.

It marked Octavian’s victory as a moral necessity and reinforced deep-rooted Roman doubts about female autonomy and oriental power.

The fate of Cleopatra’s children exposes the ultimate hypocrisy of Octavian’s promises. Alexander Helios and Tammy Philadelphia disappear from the historical record shortly after their mother’s death.

Historians debate whether they were quietly executed, exiled, or died of illness under Roman custody. Their disappearance itself is revealing.

Only Cleopatra Selai survived, and only because Octavian found her politically valuable. She was married to Juba II of Moritaia, a clerical king installed by Rome.

Through this marriage, the last living heir of the Roman dynasty became an instrument of Roman foreign policy. Even mercy, when it came, was a form of control.

The story that survives of Cleopatra’s last days is not an objective record. It is a carefully crafted narrative shaped by the victors.

The image of Ѕпa reiпa mυrieпdo coп gracia jυпto a Ѕпa serpieпte sagrada pursues multiple ideological objectives.

Romanticize the death of an enemy, making it less of a threat to history. Conceal the realities of captivity, psychological torment, and coercion.

And it allows Rome to present itself as magnificent, as if Cleopatra had been granted the dignity of choosing her fiancé. The lesser-known stories tell a much harsher story.

During the last 11 days of her life, Cleopatra was systematically stripped of everything that had defined her existence. Her political power disappeared.

His anatomy was eliminated. Their dignity is eroded through public humiliation and costless surveillance. She was subjected to emotional blackmail through threats against her children.

Even his body became an object of control, watched, examined, and regulated by his captors. The fact that he finally managed to recover a fragment of autonomy is often presented as a moral victory.

But this interpretation ignores the context. Cleopatra’s choice was not between life and death. It was between dying on her own terms or being exhibited alive by Rome as a spectacle of conquest.

This is a triumph story. It is a case study on how absolute power operates. How it reduces even the death of its enemies to political theater.

Cleopatra’s legacy was forged as much by what was seen after her death as by her actions in life. For centuries, she was seen almost exclusively through Roman eyes.

The exotic seductress, the dangerous woman whose allure undermined Roman rational virtue. This public representation was accidental. It reinforced Roman cultural superiority, justified imperial expansion, and served as a warning…